Courtesy of iii.org

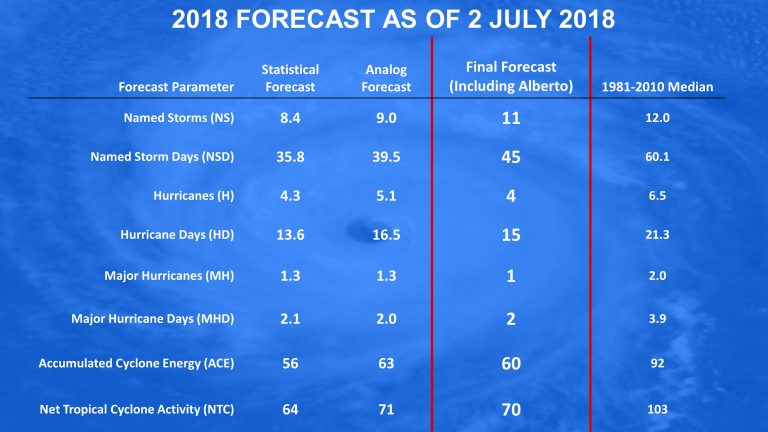

Colorado State University (CSU) released its updated outlook for the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season today, and they are now calling for a below-normal season with a total of 11 named storms (including Alberto which formed in May), four hurricanes and one major hurricane (maximum sustained winds of 111 miles per hour or greater; Category 3-5 on the Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale) (Figure 1). This prediction is a considerable reduction from their June outlook which called for 14 named storms, six hurricanes and two major hurricanes. Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) and Net Tropical Cyclone (NTC) activity are integrated metrics that take into account the frequency, intensity and duration of storms.

Figure 1: July 2, 2018 outlook for the forthcoming Atlantic hurricane season.

CSU employs a statistical model as one of its primary outlook tools. The statistical model uses historical oceanic and atmospheric data to find predictors that worked well at forecasting prior year’s hurricane activity and has shown considerable skill based on data back to 1982 ). The statistical forecast for 2018 is calling for a below-average season.

CSU also uses an analog approach, whereby the team looks for past years with conditions that were most similar to what they see currently, and what they predict for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season (August-October). The forecast team currently anticipates below-average to near-average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the tropical Atlantic and warm neutral to weak El Niño conditions in the eastern and central Pacific. This averaging of the five analog seasons also calls for a below-average season .

The primary reason for the reduction in the seasonal forecast was due to continued anomalous cooling of the tropical Atlantic. Most of the Atlantic right now is much cooler than normal. (Figure 4). In fact, current sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Atlantic are colder than any year since 1994. In addition to providing less fuel for storms, a cooler tropical Atlantic is also associated with a more stable and drier atmosphere as well as higher pressure. All of these conditions tend to suppress Atlantic hurricane activity.

CSU also believes that the chance has increased for a weak El Niño event developing to coincide with the peak of Atlantic hurricane season. El Niños tend to reduce Atlantic hurricane activity through increases in upper-level winds that tear apart hurricanes as they are trying to develop. The dynamical and statistical model guidance is about evenly split between El Niño and neutral (neither El Niño nor La Niña) conditions for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season (August-October)

Coastal residents are reminded that it takes only one storm to make any hurricane season an “active” one. For example, CSU correctly predicted a quiet Atlantic hurricane season in 1992. The season, in fact, was very quiet, with only seven named storms, four hurricanes and one major hurricane—but that major hurricane happened to be Hurricane Andrew, which tore across south Florida as a Category 5.